Just thought I’d post a concluding comment now we’ve finished the serialised reading of The Valley of Fear. Thanks to everyone who came to the reading group meetings, posted on the blog, and to everyone who read along at home. We had a really interesting meeting at Blackwells last Monday, discussing topics from Victorian gangs, text messages, the usefulness and problems of illustrations, box sets of TV programmes, depictions of England, Ireland and the U.S.A. in literature, secret identities, and nineteenth-century economics (and a few topics in between). I hope you have all found reading in serialisation worthwhile. In the group we discussed the quite novel experience of having a sense of community created by the rationed reading process, the feeling that we were all moving towards a destination together. I really found myself able to concentrate on the details of the story, or at least mull over them, in a way that I do not always afford myself when reading a whole novel whenever I want. It seems to me that such a gradual and measured way consuming entertainment or art is becoming rarer and rarer; even the way we watch television is moving away from this model with the advent of box sets and online streaming. I do hope it proved an interesting experiment for all of you who read along; let me know what you thought of it, and whether you would be interested in doing something similar at some point in the future.

Another thing I was hoping that the group would achieve is to make us think about how people consumed literature and entertainment at the start of the First World War. When the literature of the War gets discussed, as it frequently is at the moment with so many centenary remembrance projects, people tend to focus on the famous war poets. With The Valley of Fear I was oping to perhaps shed some light on what people were reading at the very start of the war, on a snapshot of popular entertainment at the time. I would be interested to hear whether this changed they way that any of you think of or imagine British wartime culture. Arthur Conan Doyle reportedly regretted handing such an ostensibly inconsequential story to the Strand, rather than one which addressed the global conflict during which it was published. But interestingly enough, in our reading groups we frequently came across readings of the tale that suggested it commented on domestic and international politics more than even its own author gave it credit for!

So, again, I hope you enjoyed the group. For those of you coming to Holmes for the first time, I hope this has enthused you to carry on reading about him. Was he as you imagined, or a different character entirely? For those old Holmesian hands I would love to hear if this serialised reading has shown you another side of the great detective. I am always glad of some Sherlock Holmes, Conan Doyle, Victorian/Edwardian conversation, and so this site will remain up and running for a bit in case anyone wants to carry on the discussion. I shall be visiting it regularly, so if there are any burning points or questions on you mind please do feel free to post a comment.

All the best, and cheerio,

David

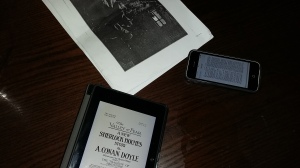

PS. Here is a snapshot of the some of the different ways those of us at the reading group were reading along with The Valley of Fear: paper, kindle and phone. Slightly different from when it was originally published!